Streams of Gold, Rivers of Blood and the difficulty in writing about Byzantine history

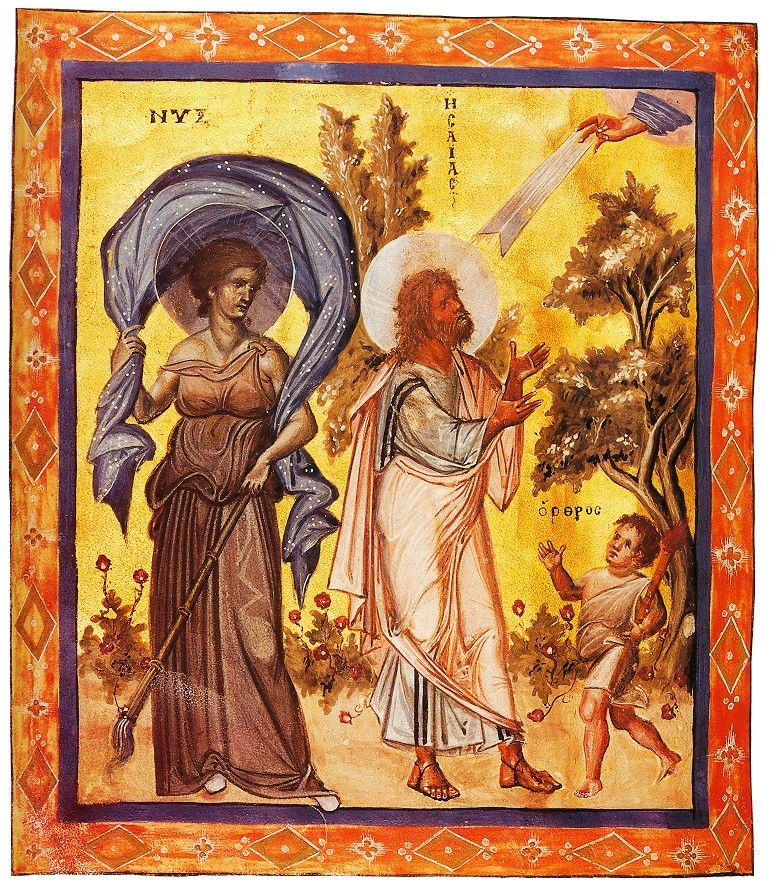

Byzantine history is unique in that we get to see a pagan culture transition into a Christian culture that transforms the way that they looked at the planet and their place in it. One of the questions that I find myself asking is how their ethics changed due to the adoption of Christianity. Most importantly, how did the Byzantines change their ethics towards violence and the conduct of war? Were they as brutal as their Roman ancestors? This is a crucial question as it allows for us to determine whether Christianity made any impact on Byzantine ways of warfare.

The historian, Anthony Kaldellis, is one of my favorite authors on the topic of the Byzantine Empire, especially on the psychology of the Byzantines. He is among one of the preeminent Byzantinists of our age. His books are the kind of narrative history that are needed to get people interested in Byzantine history in the first place. One of his greatest books that he has written is Streams of Gold, Rivers of Blood that was published in 2019.

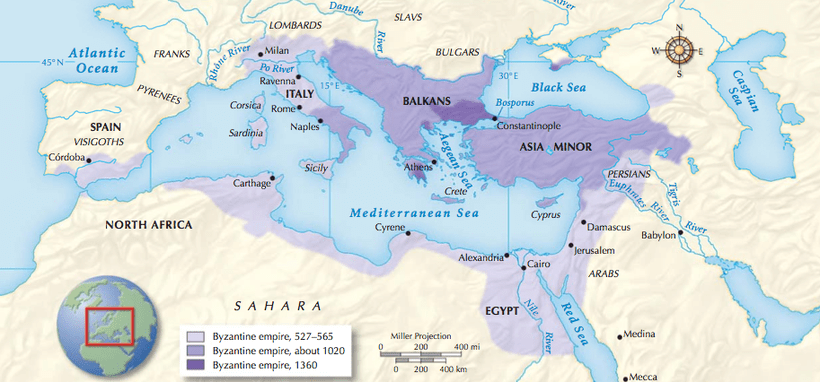

In comparison with most books written about the Byzantine Empire, this is the first book since the late 19th century to focus entirely on the years of expansion and contraction between the years of 955 and 1081. The fact that a book on this period has not been published for some 120 years shows that Byzantine history remains largely obscure to the eyes of the public.

Streams of Gold, Rivers of Blood is one of the finest Non-fiction books that I have read. It is important to remember that over the past couple of decades, many stereotypes have developed about the Byzantines and clung on, despite the efforts of many historians to refute them. Anthony Kaldellis does a good job at presenting a side to the Byzantines that is generally not commonly understood. This side of the Byzantines that I am talking about is their renaissance in the 10th and early 11th centuries. Generally speaking, when people think about the Byzantines, they are thinking about the reconquests of Justinian in the 6th century. After that, Byzantine History tends to be skipped over in the history books, at least in the Western countries. However, Mr. Kaldellis does a good job at creating a new narrative behind the idea of Byzantine resurgence in the 9th, 10th and 11th centuries.

The idea of Byzantine resurgence is an incredible one, as it is a story that we often do not get told by the historians and popular media. I am happy that it is finally getting told after so many years of being obscured by the sands of time.

However, there is a section of the book that I found very interesting and that is the beginning in the preface. The words that the author uses to describe the Byzantine people is that they were not a warlike people. This struck me as odd, considering that Kaldellis’ book is focused on the resurgence of Byzantine fortunes and that involved a great deal of violence and conquest. The Byzantines were living in a world where their empire was built like a fortress. This was not the Roman Empire of Augustus where one could walk all around North Africa and be able to trade and engage in commerce unmolested. They could not afford to be nice with their enemies. They were being attacked constantly by Arabs, Pagan invaders, Normans of all stripes. After Heraclius, they had to build their empire like a fortress to maintain their empire.

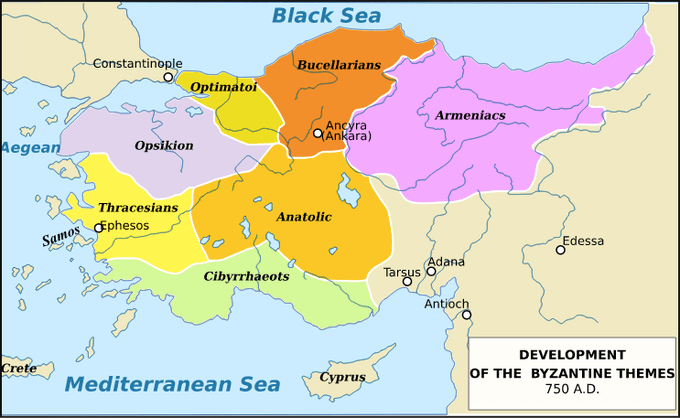

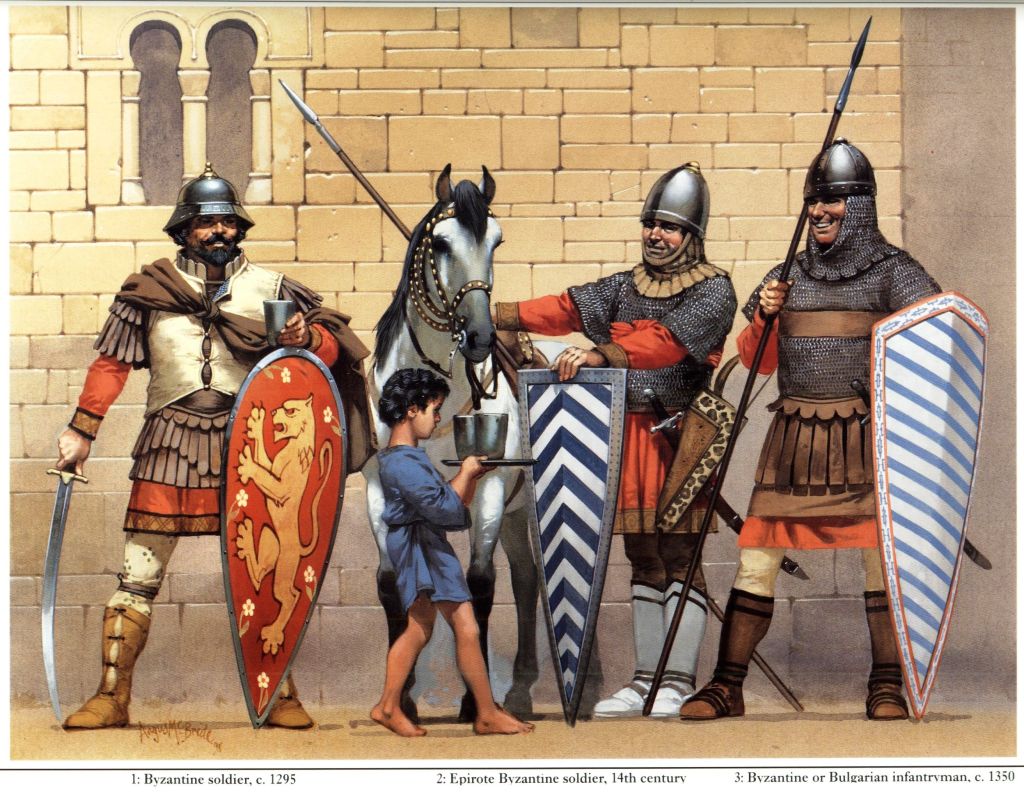

This fortress system involved reorganizing the whole military. The themes contained thematic troops who came from what remained of the Roman field armies of the Eastern Roman Empire (before the rise of Islam). A professional core of troops called the tagmata would also be established in order to supplant these troops. What occurred here is that the regional commanders became more responsible for the security of their local fiefdoms. As a result, Byzantine society became more militarized and local than had been the case in the Eastern Roman Empire during the times of Theodosius and Justinian. The government was still highly centralized compared to Western Europe, but these changes were altering the way that Byzantines looked at themselves and their position on the political stage. If one wants to take a long look at the tide of Roman history, this militarization had been going on since the crisis of the Third Century had convulsed the Roman Empire and almost resulted in the downfall of the entire government.

So in a sense, the Byzantines became a culture that was always on defense, sometimes on offense, but always looking behind their shoulders for plots.

I decided to take the time to explain to you the many contradictions that are inherent in the Byzantine approach to war.

The Byzantines. Were they warlike?

It is clear that any historian that is writing about a particular historical topic is going to have a bias about it. The Byzantinists in us are going to want to portray the Byzantines in flattering lights and generally speaking this is because we want to have someone to root for in history. Mr. Kadellis, obviously wants us to think about the Byzantines in a way that is positive and not negative. They want people to learn about how the Byzantines were not just oriental despotism but something that represented a reformed Roman culture that moved away from the violent Pagan ways of their ancestors. That’s the ideal they want us to think about. However, the reality is much murkier than that.

The Early Middle Ages, especially towards the beginning of the Crusades, was an era of endemic conflict across Europe. The Middle East and North Africa tended to be more orderly and quieter but still had their conflicts and civil wars. Europe at this time was a motley collection of kingdoms and small merchant republics. These states often fought against each other and were decentralized realms.

In comparison, the Byzantine Empire was centralized and had a more homogenous population than most of the empires surrounding it. According to the book, Streams of Gold, Rivers of Blood, the Byzantines were more of kingdom and less of an empire. They were the closest thing that the Medieval era could get to a nation-state before its rise during the post-Westphalian era of the 17th century.

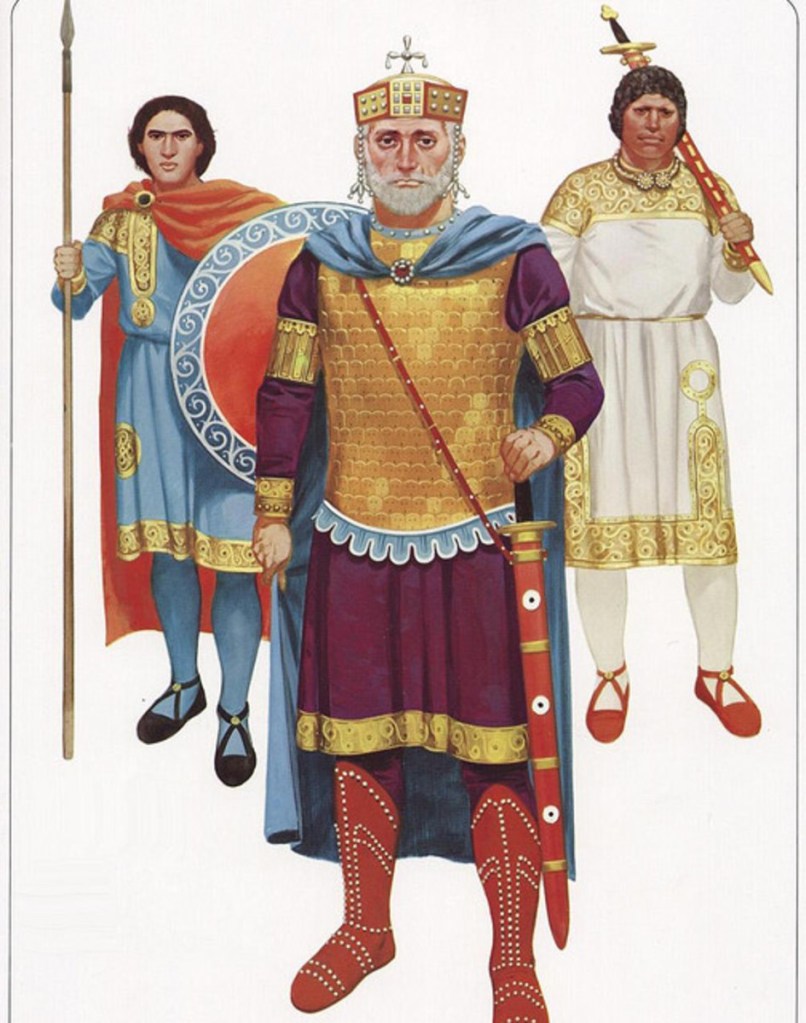

The Byzantine state, while being more centralized and homogeneous than its medieval contemporaries, this did not mean that the empire was free from conflict. Streams of Gold, Rivers of Blood describes this perfectly: The Byzantines were famously defensive. The Byzantine state, the heir to the great Roman conquering legacy had to be pragmatic on the issues of defense and warfare. They thought of themselves as the holy kingdom of the divine on Earth but knew that they had to defend themselves and sometimes go on the offensive in order to pursue their own political agendas. The Byzantines, unlike their classical Roman ancestors, were not ones to enjoy war for its own sake. While there may have been individuals and organizations that were more focused on war and reaping the benefits from that, most of the society was focused on adhering the laws of divine. The Byzantine state seemed to be more focused on trying to be perfecting the intermediary kingdom that was the gateway to the realm of the divine than in trying to create one universal empire as had been done under the emperors Augustus and Justinian.

Jesus in particular was an important figure in the Byzantine Empire. Unlike the avatar of Julius Caesar and Augustus, both great conquerors, Jesus was a teacher and a man who famously said that render onto what Caesar’s is Caesar’s. His humility and sinless nature was an inspiration for many, especially those who were disastified with the current state of pagan Roman society. His teachings were transfused into the very lifeblood of the Byzantines. If you got to the Hagia Sophia or other churches in the areas that the Byzantines controlled, you will see the image of Jesus being prominently displayed on the walls and mosaics. While Jesus was no military leader and his ministry did not involve military campaigns and the changing of territory, the Byzantine state easily incorporated his image into the imperial ideology whenever it needed a symbol to rally around.

The Byzantine Empire in the early period seemed to have been particularly unstable, as its territory included a greater variety of peoples and places. The Near East and Egypt included many Christians who were not onboard with the Orthodoxy that was being promoted in Constantinople. This meant that the empire was dealing with lots instability and unrest related to religious issues. Examples of this include the Samaritan revolts in the Byzantine Empire which took place in the 5th and 6th centuries and were put down by the army. The Nike Riots, which famously took place in a wholly Christian realm, were some of the bloodiest riots in human history, with some 30,000 rioters slain in the Hippodrome according to Procopius.

The most famous of Byzantine revolts, the Jewish Revolt against Heraclius, occurred during the 7th century. It was a bloody rebellion that happened while the monotheistic Sassanids were rampaging through the region. The Jews too an opportunity to revolt and caused great harm to the Roman Empire during their war with the Sassanids. The Jews ended up helping the Sassanids deliver a moral victory against the Byzantines, and they attacked their Christian neighbors with impunity. The True Cross was captured, and religious violence began erupting all across the Near East. Even when the emperor Heraclius recaptured these territories around 628 AD, these areas would remain restive and revolt against the Byzantines again when the Muslims came knocking at the door.

Clearly, even with the adoption of Christianity, the Byzantine realm still retained the usual pretensions of imperial glory and conquest that typified the pagan Roman Empire. The Byzantines were very willing to use an army to put down a rebellion of Samaritan, Isuarians and Jews whenever things got out of hand. The results of these conflicts could be very bloody and indeed, the Byzantines of this era had a lot of blood on their hands. Justinian’s wars of reconquest in the 530s to the 550s were notoriously bloody affairs and it is not surprising that the Eastern Roman Empire during this period of time largely continued the violent ways of putting down disputes in the Empire with bloody efficiency.

Even when the empire began shrinking in size and became more homogeneous and Greek in its composition, there were still tons of rebellions amongst themselves. One just has to look at the Twenty-Years anarchy to understand the instability that would convulse the Byzantine Empire. There was a total of six emperors over a period of 20 years. There were coups and countercoups. The fact that the Byzantine Empire did not collapse during this period is probably due to the military organization of the empire.

The Age of the Macedonians

The Macedonian Dynasty was a period of time in Byzantine history when the sun began shining on the empire once again. The empire clearly had been defensive for the past 250 years since the days of Heraclius and his defeat at the hands of the Muslims at the Battle of Yarmouk. The Byzantines and the warlike nature that is inherent in every imperial power throughout human history was put on hold for now.

There were many steps that were required to get to the greatness of the Macedonian age. First, the Byzantines had go through a series of sieges on their capital, go through the Twenty-years Anarchy and then go through the two phases of Iconoclasm, before they managed to arrive at 867 and able to start expanding their empire.

So how warlike were the Byzantines in this period of history compared to say the 6th century?

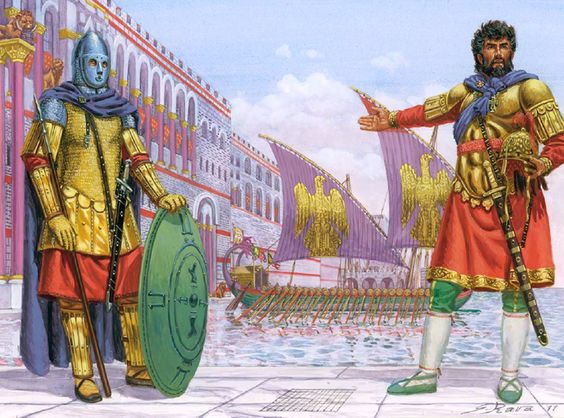

The Byzantines, much like any medieval power, was a state that had most of its budget focused on the military. The church and its holdings were a distant second, but the military was the most powerful and most dangerous aspect in the hands of the emperor. The Byzantines were governed by Christian ethics, so the church had something of a limiting influence on the depravities that could inflicted on enemy armies, but the Byzantines were pragmatic people as well as idealistic. Their enemies, many of whom were pagans, were known for their brutal tactics in warfare. For instance, Khan Krum of the Bulgarians had turned the skull of a fallen Byzantine emperor into a drinking cup after the Battle of Pliska. The Byzantines were exposed to these methods, and probably thought them to be work of savages. However, the Byzantines during this period were also known for being more aggressive and employing cruel tactics on their enemies.

Byzantine military strategy generally speaking from Maurice’s Strakegion to the manuals of the 10th century tended to emphasis defensive tactics over the offensive tactics of the Roman principate. Defense in depth was the order of the day in the Byzantine Empire and this was about to change with the rise of the warrior emperors in 10th century.

Emperor Basil, I founded the Macedonian Dynasty, though for the next 60 years up to the 950s, the Byzantines would remain incredibly entrenched in their defensive nature. This would begin to change in the 950s, when the warrior emperors would begin to reenergize the military ethos of the Byzantines.

According to Kaldellis, the Byzantine military philosophy was not influenced greatly by Christianity. He states: However, religion did not predetermine or even shape Imperial strategy and military objectives. There was no difference in how Roman armies treated Muslims or Christians. Kaldellis emphasizes that ”Orthodoxy was the rhetoric or cultural style in which pragmatic policies were expressed.” This is a very important point. The Byzantines were pragmatic about the enemies that they were dealing with. There were constant struggles with the Bulgarians to the north and the splintering Arab world to the East. Orthodoxy was often the way in which what we see as pragmatic approaches to brutally dealing with the enemy was expressed through the rhetoric of religion.

How was this practically applied in military campaigns during the 950s to the 1070s?

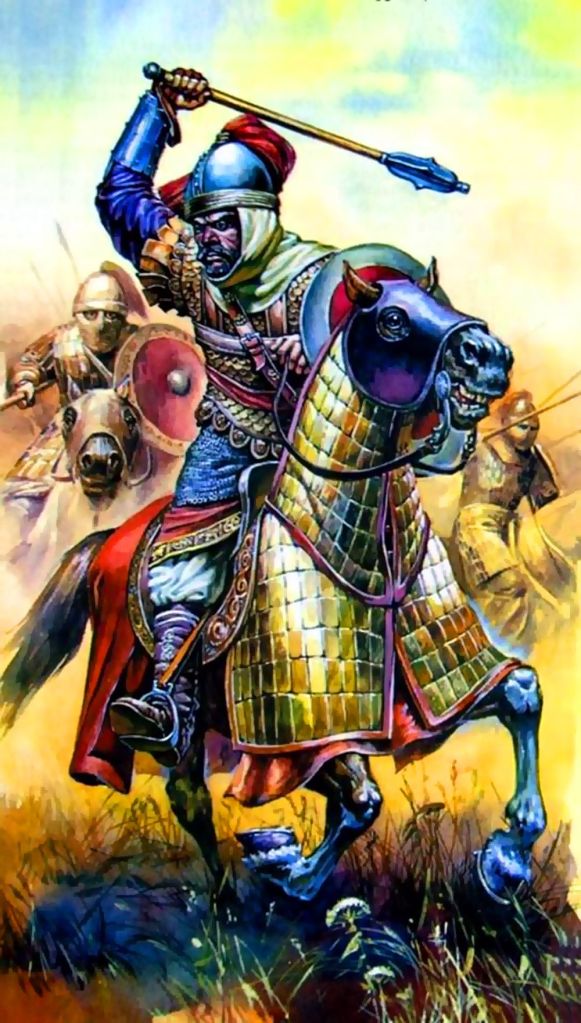

The warrior emperors were coming from a generation of men who were bred for war. The first of these emperors were Nikephoros II Phokas.

He had been very successful on the Eastern front with the Arabs, earning him nicknames that showed how he invoked fear in the minds of the Muslims. However, his best-known conquest is that of the strategically important island of Crete.

The Arabs had been using Crete as a base for raiding and abducting Byzantine citizens for decades and the Byzantines sought to put an end to it. Nikephoros II Phokas landed an army on the island and after an important siege of the city of Chandax, the Byzantines emerged victorious. One of the tactics that Nikephoros used in order were psychological weapons. He ordered his men to cut off the heads of the fallen Muslim soldiers and then hurl them into the city of Chandax. Again, these tactics were common to many Medieval armies and the Byzantines were no exception to the rule.

One of the most interesting episodes of Nikephoros reign and an insightful look at Byzantine ethics when it came to war was the emperor’s clash with the church on the issue of fallen soldiers being made into holy martyrs. While the plausibility of this episode is debated amongst scholars, it shows that there was an internal struggle in the Empire on the ethics of war in the Byzantine Empire. Many in the church rejected the Muslim view of Holy War and the creation of martyrs for the cause of Christianity. It was not until the Crusades, that Nikephoros’ ideals would be the standard practice for Crusaders fighting in the Holy Land.

Nikephoros himself was an asecetic and pious man, yet that did not stop factions at the Byzantine court from plotting to have him assassinated. The Byzantine peoples, though they may have been pious Christians, were not above to getting rid of their rivals in order to pursue political aims. John I Tzimiskes would be his successor and would also lead important campaigns against the Muslims.

However, all these campaigns against what were called the Saracens in the 10th Century were largely pragmatic concerns and not about holy war. Defending the Empire and expanding the realm were patriotic concerns not spiritual ones. However, it is clear that during this period, the Byzantines were becoming more warlike as they became invested in the expansion of the empire’s reach across many reaches of Anatolia and the Balkans.

John I Tzimiskes’ campaigns against the Arabs proved to be quite fruitful and greatly helped the Byzantines. The Byzantine goals during Tzimiskes campaigns were to unite the Christian peoples of the Levant and also to cripple the Abbasid Caliph’s grip on power. These campaigns show the difference in the mentality of the Byzantines during this time of resurgence. They were willing to go on the offensive. While the Byzantines had gone on the offensive before the rise of the Macedonians, most of those attacks were punitive and not for the reasons of taking territory. The Arab world during the time that John Tzimiskes reign was divided into multiple emirates with the Abbssid Caliphate holding only nominal authority over Arabs and other various peoples in the Middle East.

John Tzimiskes’ campaigns were so successful that he managed to rampage the emirates of the Levant all the way to Tripoli before stopping around the edges of Jerusalem. He wasn’t able to capture the city but the Romans were able to establish administrative authority all along the coast of the Levant area.

Emperor John Tzimiskes’ campaigns would be only the beginning of Byzantine military expansion during this great period. The Byzantines were just getting started with their reconquests.

Byzantine military aggression during the reign of Basil II

Anthony Kadellis was only partially right to say that the Byzantines were not a warlike people. In this particular period however, the Byzantines were fighting wars on multiple fronts, taking the sword to enemy rather than hiding behind their walls. No emperor better exemplifies this period of military expansion than Basil II.

Basil II was a minority during the time that John Tzimiskes was in power, but when Basil II came to power in 976 at the time of John’s passing, the Byzantine Empire had not yet reached its medieval apex.

Basil II is one of those legendary Byzantine emperors who managed to deal with the twin enemies of the Bulgarians and the Fatimids. He managed to do all of this at the same while fighting a civil war that was being led by Bardas Phokas and Bardas Skleros.

The Byzantines were engaged in many wars during this period; this should go to show that the Byzantines were in a new phase of their history. They were no longer on the defensive.

Sources for this period of history are rather sparse and lacking. However, like all medieval states, the Byzantines during this period were engaged in endemic warfare for survival against their foes. While the Byzantines were very much used to using diplomacy and soft power to influence the peoples’ arounds them, they were very keen on using hard power to get what they wanted. Especially considering that their enemies were not going to be letting their guard down, the Byzantines during this period were smart to be going on the offensive.

One of the most famous examples of brutality still being the mode of how they conducted themselves during war was the mass blinding of Bulgarian prisoners by the emperor Basil II. The Bulgarians had been fighting Basil II for years and years and yet the Byzantines emerged victorious in battle.

After the Battle of Kleidon, in which the Bulgarians were defeated by Basil II, the scholars of the age stated that Basil II committed one of his most gruesome and outrageous acts. He ended up having thousands of Bulgarians blinded, with only a few spared in order to lead the others home. When his great rival, the Emperor Samuil of the Bulgarians saw what remained of his army, it said that he passed away due to a heart attack caused by this sight.

Whatever the historical legitimacy of this, the fact that the story circulated showed that the Byzantines were very much capable of brutality even if they did not practice it for its own sake.

By the time of Basil II’s passing in 1025, the Byzantine Empire was at its apex in size, wealth and power. However, quickly, the Byzantines would find themselves begging the Pope for help and this would launch the Crusades.

Overall, the idea that the Byzantines were not a warlike people is something that is murky and much more complicated than it seems at first. The Byzantines treat war as pragmatic, which separates them from the Muslims or the Latin Christians of the West. Unlike their Roman ancestors, war is something that results from the failure of diplomacy, not something that is to be enjoyed for its own sake. The Byzantines, when they did engage in warfare, practiced many of the depravities and atrocities that accompanied many Medieval armies. However, they often did this under the glamour of Orthodoxy. The Byzantines were human like all of the people in history and their story is one of ideals meeting the harsh realities of life in the Middle Ages.